This year marks the centenary of both the death of Marcel Proust and the publication in English of the first volume of his masterpiece “In Search of Lost Time”.

The novel “In Search of Lost Time” is widely considered by scholars and critics to be one of the greatest modernist novels of all time, it won the contemporary admiration of Virginia Woolf, BBC reports.

"Oh, if I could write like that!" she exclaimed in a letter to Roger Fry in 1922. Like Woolf and James Joyce, who would publish their own groundbreaking novels that year, Jacob's Room and Ulysses respectively, Proust spectacularly broke with the realist and plot-driven conventions of 19th-Century literature in order to create something entirely new. So new in fact that to this day it remains profoundly misunderstood.

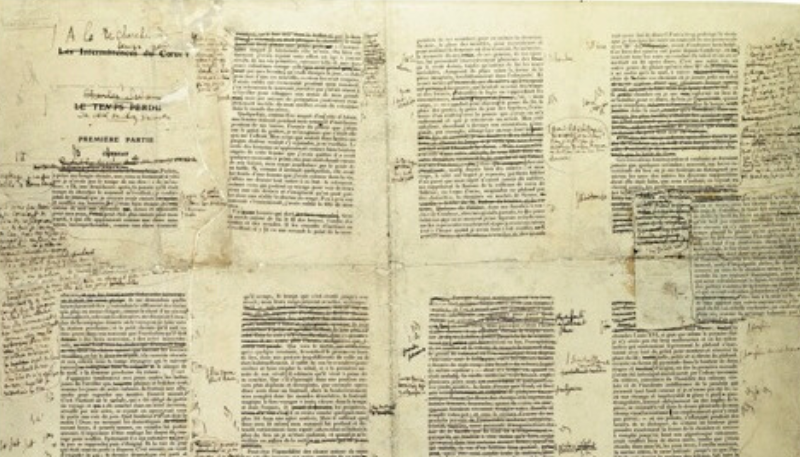

As with Joyce's Ulysses, In Search of Lost Time's length (it's officially the world's longest novel) and perceived complexity mean that far more are likely to have heard of the clichés surrounding the work than have actually read it. We may think of madeleines dipped into tea conjuring reminiscences of the past, prohibitively long sentences and Proust himself, with his languidly drooping eyes and dandyish moustache, cooped up in his cork-lined bedroom working obsessively on his magnum opus. All this may lead us to believe that the work is an impenetrable, overly long, aesthetic indulgence to be enjoyed only by a small number of highbrow individuals who wish to demonstrate their cultural credentials. In that, we would be very much mistaken.

Christopher Prendergast, editor of the Penguin edition of “In Search of Lost Time” and the author of several books on Proust including the recently published Living and Dying with Marcel Proust, acknowledges the difficulties of summarising the novel. "Proust's fictional world is expressly and intentionally a world in a state of constant flux. It self-transforms and self-displaces and that makes it radically resistant to any kind of quick synopsis," he tells BBC Culture. However, when pressed to attempt a brief outline he notes that despite its experimental nature, there is still a basic narrative weaving throughout the novel. "It tells the story of a person from boyhood through to somewhere late in middle age and culminates in the discovery and embrace of a vocation, which is the vocation of a writer," he says. This narrative places the novel in the tradition of the European Bildungsroman, the story of the formation of an individual from youth to maturity.

That formation entails many years of disillusionment and disappointment. As Prendergast points out the "perdu" in the original French title, À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, means both "lost" and "wasted", a nuance it is impossible to capture in an English translation. From an early age, the narrator yearns to enter the high society of the Guermantes family, but this proves to be shallow and snobbish when he finally gains admittance. His love life is equally disappointing, leading to one disaster after another, especially regarding his relationship with the free-spirited Albertine, who he first encounters as a young woman while on holiday and later ends up keeping virtually imprisoned in a tragic illustration of the destructive nature of sexual jealousy. This is all "accompanied by the sense that the narrator has of wasting his time, that there's something out there that awaits him, that he can semi-identify as something to do with the project of becoming an author or writer… but he keeps detouring away from it, so he's wasting his life until he gets to the point where he suddenly realises it and embraces it," explains Prendergast.

The narrator may consider his lived experience "wasted" – of course, it is not and will eventually form the inspiration for his novel – but the reader is never likely to concur. As the late Proust scholar Roger Shattuck wrote in Proust's Way, his "field guide" to In Search of Lost Time, this "superficially forbidding novel" contains an "a world of vivid places and intensely human characters" which combine to make it "the greatest and most rewarding novel of the 20th Century."

As we accompany the narrator on his journey, we enter a world in a profound state of flux traversing the decadence of the Belle Époque, the social and political ructions caused by the Dreyfus Affair and the trauma of World War One. The many memorable characters we encounter include the refined Charles Swann, whose obsessive love for the former courtesan Odette foreshadows the narrator's relationship with Albertine, and their daughter Gilberte, who will be the narrator's, first love. Gilberte will later marry the dashing Robert de Saint-Loup, himself a member of the illustrious Guermantes clan, which includes the glamorous Duchesse de Guermantes and the boorish, closet homosexual Baron de Charlus. Their glittering yet ultimately the shallow world is seen to gradually give way to a philistine, bourgeoisie epitomised by the vulgar, hypocritical Madame Verdurin and her "little clan". Her shocking rise to become the Princesse de Guermantes in the final volume reveals how economic and social shifts mean that wealth alone is now capable of eclipsing birth when it comes to status.

This revelation comes during the celebrated Bal de Têtes scene in which the narrator, having been absent for many years, encounters the surviving characters of the novel. Prior to entering the event a series of intense memories, akin to those inspired by the taste of the madeleine, dramatically reinvigorate his sense of vocation. He realises that the subject of his great work is to be the loss of his calling and the lengthy journey to retrieve it. Once he discovers that he is unable to identify any of the figures who are to be characters within the work, as they have now aged beyond recognition, he is disheartened but is saved by his introduction to the youthful Mademoiselle Saint-Loup, the daughter of Gilberte and Robert. She reminds him of his own youth and helps restore his sense of purpose. The narrator and author are now one and the same.

Its 'universal appeal'

The novel we have just read, which we assume is the novel the narrator has written, is far more than an account of one man's journey to maturity. As Shattuck notes, "the novel unfolds a lifetime of experiences, which enlarges our understanding of love and nature, memory and snobbery." It also offers hope to all those who think their own lives have been "wasted" because they have not yet found their own purpose in life. If nothing else, it emphasises that is never too late to embrace your true vocation.

If the novel's contents are often misunderstood, so to is the nature of its readership. The idea that it might only appeal to a select few is something disproved by Proust Lu, the remarkable project of French filmmaker Véronique Aubouy. Since 1993 she has been filming individuals reading roughly two pages of the book at a time with the intention of filming the entire novel in this way, a process she imagines will take another 30 years to complete. Having initially approached relatives, friends and colleagues for readings, the circle grew to include market traders, cleaning ladies, a distant cousin of Proust's and even the actor Kevin Kline. Some, like the secretary who in her spare time has translated the novel into Slovenian, are already firm fans. Others who were randomly approached for reading have gone on to embrace the whole novel. "They recognised themselves in the book and that was always Proust's goal. He said 'my readers will not be my readers, but their own readers, my book will be nothing but a kind of magnifying glass through which they can read themselves," Aubouy tells BBC Culture.

Those wanting to read a passage for the film can now apply via a form on Aubouy's website on which she asks them to state why they wish to participate. The most common reasons people give are that they have never managed to begin Proust, and this will be a way to do so; they love it and want to pay tribute to it; or they simply want to be a part of such a huge project. But there are also more personal reasons, such as it being the favourite book of a beloved relative or that they read it 30 years ago on a boat with their lover. "Such motivations result in real love poems to Proust," says Aubouy.

In an age of myths about reduced attention spans, the novel's length could seem to be offputting, but that is perhaps another misconception. As Anne-Laure Sol, curator of the Musée Carnavalet in Paris, which houses a recreation of Proust's bedroom points out: "The time spent reading Proust, compared to the time some of us may devote to watching the entire run of a TV series or scrutinising social media, is not that considerable, and it seems to me that the benefit is something else." Like Aubouy, she also stresses the universal appeal of the novel. In reading it we can enter a world which allows us to "question the role of art, experience the joys and sufferings of love, of friendship and discover an extraordinary, and often comical gallery of portraits whose manias and characters are those of our contemporaries," says Sol.

Prendergast notes that it is a common reading experience to get through the first 50 or 60 pages of In Search of Lost Time and then just give up, the lengthy sentences and inconclusive narrative proving too much for many. But he believes perseverance is worthwhile. "I used to say to my students, 'don't do that, if you persist something will happen to you'. It's the very thing that happened to me – you will become addicted. And that is indeed what happened to them."

Those who do persist will encounter a novel which in the words of Shattuck "seeks to show us the springs of life – not in a work of art but in ourselves". As such, the time spent reading it can never be wasted.