Indeed, in today’s world every modern political system could not operate effectively without the aid of mass media.

Therefore, it is believed that there will be variation in press freedom depending on the type of government that is in operation since political regimes are characterized by the political, legal and economic context within which news coverage exists.

Media plays a crucial role in influencing the mindset of the masses, in constructing/communicating and generating ideas/discourses originating from mass of population across the globe.

Now that media is busier than ever before with the freedom that can convey a message to people across the globe in a matter of seconds, thanks to the internet and the social media, there are autocrats who are equally active in the practice of media control.

According to a survey, the year 2024 will be the year of many elections with more than 60 countries voting. And this is to mean that the world will also observe how autocratic power responds or deals with media.

Historically, autocratic regimes have been manipulating media landscapes to consolidate power, overthrowing the universal struggle for democratic integrity and human rights. Autocrats imitate tactics for controlling the free press, learning from one another. They want to dictate the story and stifle other opinions to stay in power.

With the media control in play, in many countries, democracy has remained only beautiful ideas imprinted on books and sometimes even in constitutions.

Interestingly, even partial media freedom (control) yields better results in stabilizing autocratic governments, fostering transparency within ruling coalitions and managing elite expectations. The autocrats balance their need for power and the strategic advantage of limited freedom through this paradoxical constrained/barred freedom of media.

Complex web of authoritarian media control

Under authoritarian rule, media control is one of the most powerful strategic instruments to consolidate power and to maintain stability. The complex dance between autocrats and media can be characterized by a dual strategy of personnel management and censorship. To have complete ownership over media, loyalists are appointed at key positions in national media, as seen in the regimes like the USSR and China's Soviet-style Nomenklatura system.

In contemporary times, Myanmar and Eritrea employed the same techniques to bar the freedom of media. This tactic ensures that the media gatekeepers are aligned with the regime's ideological stance and that the same narrative is repeated.

On the other hand, censorship imposes stringent control on contents, a tactic historically used by the USSR's Glavlit to enforce ideological conformity. Similarly, the restriction on non-state media publications imposed by Myanmar until 2011 illustrates how controlling the frequency and scope of media output can suppress dissent and control the narrative.

Why do authoritarians control the media? First, social media platforms — especially in nations where mainstream media is closely monitored — have emerged as powerful tools for practising free speech and civic activism.

Despite the difficulties, social media platforms continue to influence regime stability to varying degrees, depending on government censorship and control levels.

Second, many authoritarian regimes have maintained or intensified their control over both mainstream and digital media, even though the use of social media has increased. Countries like Eritrea and North Korea continue to exhibit some of the strictest media controls.

Third, some countries have experienced incremental improvements in media freedom such as Myanmar and Uzbekistan.

This partial liberalization reflects a strategic act opted by authoritarian regimes to manage dissent and maintain legitimacy while keeping tight control over the media landscape.

Finally, the interaction between media control and regime stability highlights that while social media can offer avenues for dissent, regimes often adapt their control mechanisms to mitigate the impact of media freedom on their stability.

Role of media freedom in sustaining dictatorships

Controlled or governed media freedom can paradoxically strengthen the autocratic regime’s grip on power. Power is often shared with a carefully selected group of elites who along with the dictator maneuver the narrative and ideology of the state.

This power sharing scheme requires a level of transparency ensuring that all parties perceive the system as fair and stable.

To mitigate any risk of dissatisfaction and rebellion within the ruling coalition, the transparency on how resources are allocated and distributed among elites, is necessary.

Dictators impose censorship on media to sustain dictatorships by controlling historical information, suppressing dissent, and manipulating public perception.

Historically, dictators always found a way to use censorship and propaganda as a tool to strengthen their power, for instance in regimes like the Soviet Union.

Journalists often face self-censorship out of fear, which leads to a loss of critical information about autocracies.

However, journalists often find a way to resist despite the chance of facing severe repercussions, as seen in Brazil’s military dictatorship. Although media censorship is a tool for autocrats, it can also provoke resistance.

This shows the complex interplay between repression and the quest for truth in authoritarian contexts.

Analysis of media control and democratic decline in authoritarian regimes (2010-2024)

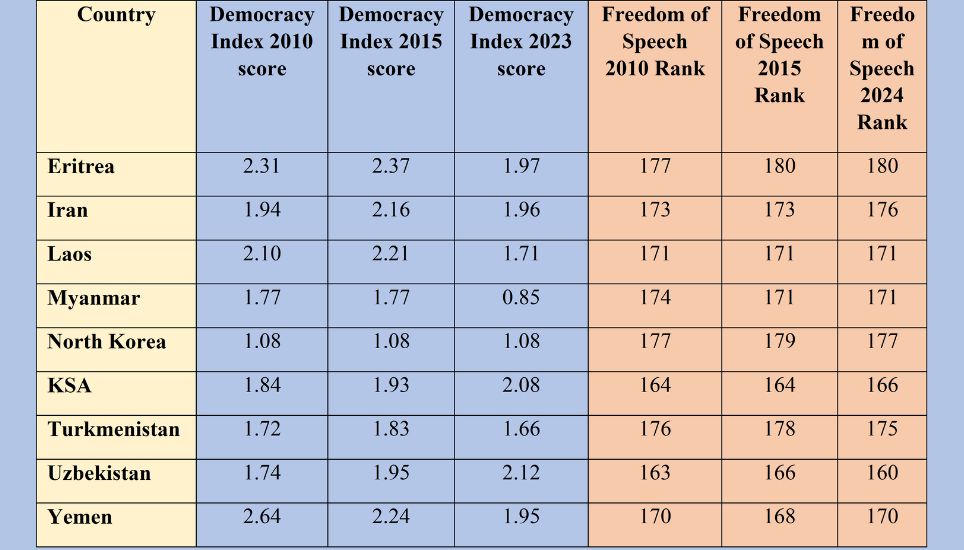

The examination of the Democracy Index and Freedom of Speech rankings for countries such as Eritrea, Iran, Laos, Myanmar, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Yemen from 2010 to 2024 reveals a worrying convergence between deteriorating democratic standards and increasing media control.

Characterized by low Democracy Index scores, these nations reflect a trend of escalation of authoritarianism. Uzbekistan's Freedom of Speech rank improved from 163 in 2010 to 160 in 2024 even though it’s Democracy Index score deteriorated from 1.74 in 2010 to 2.12 in 2023.

It is a perfect instance of how authoritarian rule can acclimatize their media governance strategy to appear more transparent while maintaining strict control over data and information.

In juxtaposition, extreme media repression can be witnessed in countries like Eritrea and North Korea, which have persistently low Democracy Index scores and Freedom of Speech rankings. This is evident from their consistently low Democracy Index scores and Freedom of Speech rankings.

Eritrea's Democracy Index score improved slightly from 2.31 in 2010 to 1.97 in 2023, while its Freedom of Speech score plummeted from 177 in 2010 to 180 in 2024.

Similarly, North Korea's Democratic Index score remained at a low 1.08, a clear indication of the regime's control over media and severe restrictions on freedom of speech. This consistent score underscores the regimes' commitment to media suppression as a tool for maintaining their authoritarian rule.

Myanmar can be considered as a classic example of authoritarian regime that preserves rigorous measures to curb oppositions and regulate the narrative and ensures their tight grip on power despite deteriorating democratic conditions.

Substantial deterioration in democratic governance can be noticed in Myanmar, where the Democracy Index score dropped dramatically from 1.77 in 2010 to 0.85 in 2023.

Notwithstanding this decline, Myanmar’s Freedom of Speech rank has a minimal change from 174 in 2010 to 171 in 2024, signifying no relaxation of media control even with ever worsening democratic landscape.

Therefore, the media freedom remains vital for the promotion of the democratic government since it acts as watchdog and enabler of free discussion within or between states.

However, within authoritarian leadership selectivity in media control and restricted openness are common occurrences as in the cases of Venezuela and Belarus.

This manipulation underlines the role of the fine line that exists between freedom of media and media regulation; a factor that plays an important role in the establishment of political systems and their sustainability or otherwise.

These forces do not merely affect the public opinion but also the political process, underlining the importance for the strong safeguards for media freedom necessary in order to preserve the principles of democracy.

The author works as a Dialogue Associate at the Centre for Policy Dialogue’s Dialogue & Communication department.