Home ›› 24 Sep 2021 ›› Opinion

That bar of soap you’re so rigorously scrubbing your hands with multiple times a day is one of the most ancient consumer products you use, with one caveat: A lot of modern soap isn’t soap at all.

Soap likely originated as a by-product of a long-ago cookout: meat, roasting over a fire; globs of fat, dripping into ashes. The result was a chemical reaction that created a slippery substance that turned out to be great at lifting dirt off skin and allowing it to be washed away.

Written recipes for soap date back nearly 5,000 years, with variations from Mesopotamia, Egypt, ancient Greece, and Rome. Here’s a method from an alchemist’s manual published sometime between the eighth and 10th centuries (even wizards who supposedly spent most of their time trying to turn lead into gold needed to do so with clean hands, apparently).

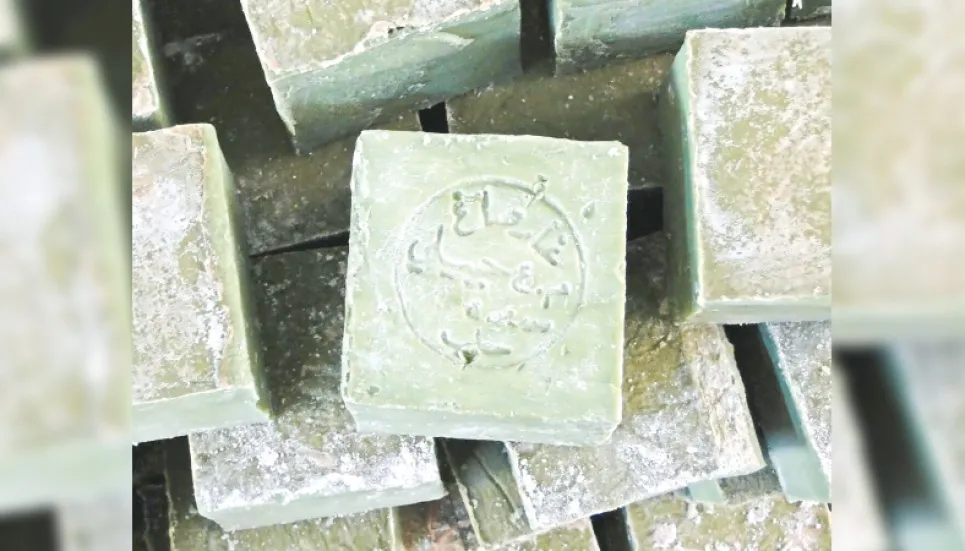

“Spread well burnt ashes from good logs over woven wickerwork … and gently pour hot water on them so it goes through drop by drop.… After it is clarified well, let it cook.… Add enough oil and stir very well.” The age-old soap recipe comes from an astonishing how-to guide called the Mappae Clavicula, which roughly translates from Latin as “A Little Key to Everything.” The alchemist’s recipe for soap calls for either olive oil or beef tallow. Tallow, or animal fat, along with lye, remains a basic ingredient of soap. Fat reacts with lye—a substance made in ashes that can be pretty toxic, which is why soap makers need to wear protective gear—in a process called saponification. The word possibly comes from the proto-German saipo, which means “to strain”; the Latin sebum, which translates as “grease”; or from Mount Sapo, an Italian mountain whose location is now lost to history. (The story is that the drippings and ashes from the cook fires of the gods rolled down the hill and were discovered by filth-encrusted Romans.)

Modern soap makers—at least those working in small, artisanal operations—use the same techniques. The saponification process yields a thick slurry. As it solidifies, fat neutralizes the caustic lye. “After 48 hours, you’ve got soap,” says Natalie Wong, of Vancouver, British Columbia’s Pep Soap, which offers both vegetable- and animal-fat-based bars.

The slipperiness of soap lowers the surface tension of the water you’re mixing it with. Rubbing your hands together while washing allows dirt to temporarily bond with the water and soap and get washed away. The same process occurs with most viruses and bacteria that might be lingering on your hands. Soap doesn’t kill these bugs—it slips them up, lifting them from your skin, mixing them with water, and sending them down the drain. This chemical and mechanical reaction makes soap and water more effective, in general, than waterless sanitizing gels.

nytimes